Ali al-Bayati clambered onto the remains of a giant winged bull statue that once stood as a protector of Iraq's fabled ancient Nimrud before the Islamic State group came.

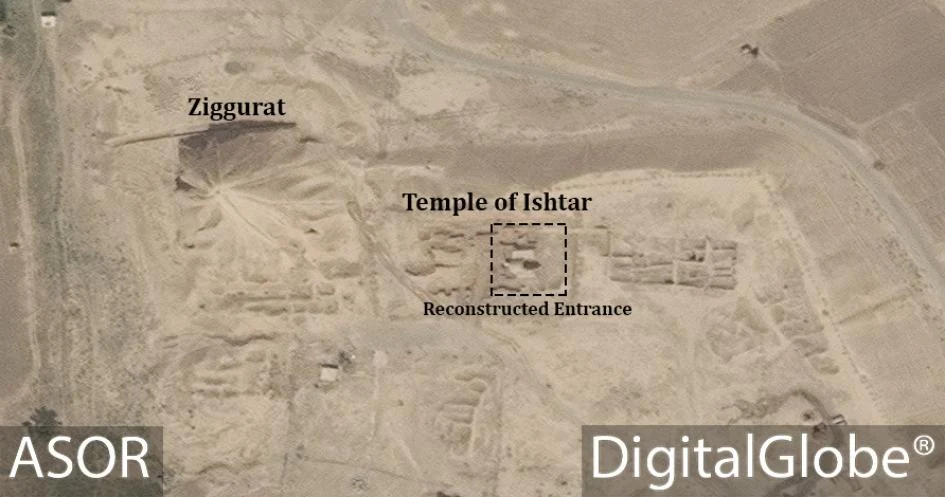

is intact. Below: A satellite photo taken on October 2, 2016 shows that the area where the ziggurat once stood

has been flattened by earth-moving equipment [Credit: ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives]

"When you came here before, you could imagine the life as it used to be," the local leader and tribal militia commander told AFP on Tuesday.

"Now there is nothing."

Iraqi forces announced that they had recaptured Nimrud -- located some 30 kilometres (18 miles) south of Mosul, the country's last city still held by the Islamic State group -- two days before.

The capital of the kingdom of Assyria some 3,000 years ago, Nimrud was one of the richest archaeological sites in the region.

But after IS took over the area along with swathes of other territory in 2014, it sought to level what remained of the city for propaganda gain.

140 feet high some 2,900 years after it was built [Credit: ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives]

The jihadist group released video footage last year of fighters blowing up the remnants of the famed Northwest Palace and smashing stone carvings at the site -- destruction it justified as wiping out un-Islamic idols.

Now it appears that almost nothing is left undamaged.

Statues lie shattered, the reconstructed palace is wrecked and the remains of a ziggurat -- once one of the tallest structures left from the ancient world at some 50 metres (yards) high -- has been reduced to a fraction of its height.

"One hundred percent has been destroyed," Bayati said as he surveyed the hilltop site, just 500 metres from his native village, for the first time in more than two years.

"Losing Nimrud is more painful to me than even losing my own house," he said.

UNESCO has said that the destruction of Nimrud by IS amounts to a war crime.

Bombs and booby traps

The group also blew up and looted antiquities in the spectacular Syrian site of Palmyra, smashed sculptures at ancient Hatra in Iraq, which is still under IS control, and rampaged through the Mosul museum.

In Nimrud, the jihadists attacked the antiquities with ferocity as they claimed they represented idols banned under their extreme interpretation of Islam.

But that has not stopped them from looting and selling such allegedly forbidden items to fund their operations.

"They want to make a new picture of Iraq -- with nothing before Daesh," Bayati said, using an Arabic acronym for the group.

He said he thought IS "destroyed this place because they wanted to destroy Iraq -- the new Iraq and old Iraq".

Most of Nimrud's priceless artefacts were moved long ago to museums in Mosul, Baghdad, Paris, London and elsewhere, but giant "lamassu" statues -- winged bulls with human heads -- and reliefs were still on site.

Now it will take experts to carry out a full evaluation of the damage IS has wrought at Nimrud.

But it may be some time before they can get there: the jihadists that Iraqi forces are fighting to drive back are still just a few kilometres away, and occasional explosions can be heard in the distance.

The site also still needs to be fully investigated and cleared by security forces of any hidden dangers IS may have left behind.

"There are many (bombs) and booby traps suspected," said Lieutenant Wissam Hamza, a member of an army explosives disposal team, as he walked carefully across the site.

"So we want to find them and clear the area -- then after that it can be called safe."

Source: AFP [November 17, 2016]